This post first appeared in Cantonese in the HK Economic Journal on 30 January.

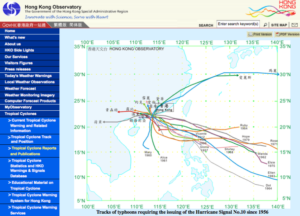

A level-five typhoon hell -bent on wreaking havoc unexpectedly changes direction. Instead of moving towards Japan, as predicted, it’s now heading straight for Hong Kong. As soon as the typhoon’s new course has been noted by local meteorologists, your trusted Hong Kong Observatory app has bombarded your smartphone with alerts, warning you to take note that the level has been raised to nine – indicating black rain. You now know to take your laptop home and prepare to stay indoors the following day, as work is officially canceled. This, and many other innovations we take for granted, is made possible thanks to open data.

-bent on wreaking havoc unexpectedly changes direction. Instead of moving towards Japan, as predicted, it’s now heading straight for Hong Kong. As soon as the typhoon’s new course has been noted by local meteorologists, your trusted Hong Kong Observatory app has bombarded your smartphone with alerts, warning you to take note that the level has been raised to nine – indicating black rain. You now know to take your laptop home and prepare to stay indoors the following day, as work is officially canceled. This, and many other innovations we take for granted, is made possible thanks to open data.

Open data is a relatively new concept in Asia and most governments in the region are wrestling with how to best include it in their national economic and technological strategies. With the exception of a few countries, most of the data Asian governments hold is closed, meaning users are limited in the reuse or analysis of valuable public information. In some cases, you might even be breaking the law by hosting government statistics on a site. When data becomes open, all this changes. Coined ‘a new goldmine’ by The Economist for its usefulness, open data has an estimated annual economic impact globally of at least USD $3 trillion.

Open data has the potential to unlock a bounty for Hong Kong that can be applied in a plethora of highly constructive ways, in addition to a significant economic impact. The socioeconomic benefits from liberating public data alone are substantial; the free flow of information and data reduces the friction that slows down development in both emerging and advanced internet economies like Hong Kong’s. More specifically, a country that fully embraces open data will see tangible gains in its creative, entrepreneurial, and innovative output – aspects crucial to sustaining Hong Kong’s long term prosperity.

According to the World Bank, Hong Kong currently ranks fourth in East Asia and Pacific and 18th in the world for its Knowledge Economy Index, ahead of Japan, Singapore, and Korea. This shows that the city is doing a commendable job to ensure its Internet environment is conducive for knowledge to be used effectively for economic development. Yet, quantitative rankings alone are not enough to fully portray a country’s open data preparedness and many facets of Hong Kong’s ICT sector requires attention to ensure users are well-equipped to convert data to gold.

Hong Kong has made tremendous progress in embracing open data and connecting hungry coders with a feast of public sector data sets. For example, the establishment of a Public Sector Information portal, Data.one, and in 2011 the Hong Kong government released selected data sets to the public provided by government departments. In addition, in 2011 and 2013, the government launched app competitions with the ICT community to encourage software developers and IT students to develop ideas and solutions based on the published data sets. The most recent competition yielded 100 contributions, of which 22% of the submissions were based on traffic, 16% on weather, and 12% on air pollution data sets.

While app competitions are a good way to encourage user participation with public data sets, Hong Kong is not actively engaging the community through a dynamic exchange between stakeholders from the supply and demand side. Creating a dynamic community for developers and end users to collaborate is essential for the sustainable development of a market’s Internet economy. Taiwan, for example, is one of the few countries in the Asia Pacific region to have successfully combined information push and pull elements in the open data environment, thus enabling a dynamic market for data. They have achieved this through aggressive community engagement and collaborations between the government and wider business and civil society, in addition to partnering with the UK open data Institute to bring about more liquid Internet economies.

On the regulatory side, Hong Kong faces some challenges. The city currently lacks comprehensive access to information laws as well as copyright regulations that would provide users a sound basis for business built on public data. Recognizing the need for a stronger regulatory environment to protect intellectual property and encourage innovation, the Law Reform Commission is currently reviewing a revision to the city’s information laws and the government recently proposed a series of initiatives under the theme of “Smarter Hong Kong, Smarter Living” in an update to the Digital 21 Strategy. As part of the new Digital 21 Strategy, the city will make, “all government information released for public consumption in machine-readable digital formats from next year onwards to provide more opportunities for the business sector.”

While these initiatives are progressive actions, the recent call from the Hong Kong Privacy Commissioner to extend the ‘right to be forgotten’ to Hong Kong and Asia threatens to reverse all our nascent progress on open data in Hong Kong. The right to be forgotten will open up holes on the internet and search engines in particular, hurting businesses’ access to this “marketplace of ideas” for data-driven innovation, and users’ access to information as well as right to know. This takes us in the wrong direction of progress; the destruction of information has an adverse affect on the betterment of our economy and overall society.

Open data is empowerment. The more access people have to public data sets, the more new ideas and innovative solutions tailored to the needs of society are developed, effectively unleashing a significant business impact while simultaneously elevating Hong Kong’s overall competitiveness. The wider business, ICT and academic communities are just starting to get involved in Hong Kong’s open data development, now is the time to galvanize an unobstructed flow of information for all.

Waltraut Ritter is a member of Open Data Hong Kong, a managing partner and research director of Knowledge Dialogues, which she founded in Hong Kong in 1997, and a member of the government’s Digital 21 strategy advisory committee.